The conversations we’re engaged in today are like a breath of fresh air. We’re finally talking openly about complicated issues and diving into how race, gender, and identity affect our communities at large. If we are going to spark real change, we must acknowledge that these lessons start early. Arguably, the first introduction of bias, privilege, and stereotypes begins with the toys our children play with each day.

Toy brands have struggled with representation for decades, and it’s understandable why. With a market that is reliant on the sentiments of both child and parent, toys need to have dual appeal. But these issues become complex when toys are made to look like and act like real people. But look and act like who?

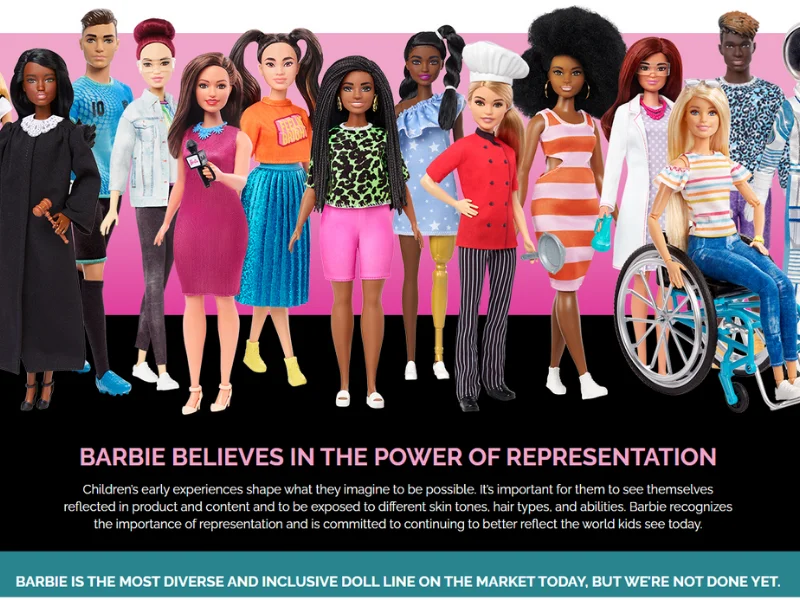

Like today, toy manufacturers in the early 1900s made products that reflected the times, and those times were fraught with gender and ethnic-based stereotypes that were nurtured and reinforced over generations of play. It wasn’t until the 1960s when mainstream brands like Mattel and Habsro started to create dolls and action figures for people of color, and only in the last few years were lines expanded to be more inclusive. Decades later, Mattel took on what they considered a risky venture and released Barbie dolls of various skin tones, body sizes, hair textures, and eye colors. Their risk paid off in dividends proving that all children (and their parents) like to see themselves reflected in the toys they play with each day.

Representation Matters

Mattel was very forward in its thinking. It understood the promise of little girls when it first launched Barbie in 1959, and it also came to understand African-American buying power despite the wealth gap. In 1968, Mattel acted as a venture capitalist/incubator of sorts to a black-owned company called Operation Bootstrap based in Los Angeles that wasn’t even in the manufacturing business. Founded in 1965 after the Watts Riots in Los Angeles, two enterprising individuals, Louis S. Smith II and Robert Hall created a cooperative focused on black empowerment and jobs. Mattel happened to be their neighbor.

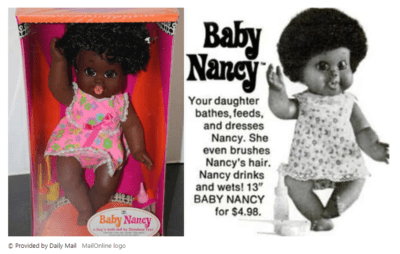

Their success piqued the interest of Mattel leadership and led to a joint venture called Shindana Toys. This new black-owned company would make toys for African-American consumers that “reflect Black pride, Black talent, and most of all, Black enterprise.” You can read the details of the who, what, and why here and here. But the main point of this story is that Mattel realized the economics of representation, acknowledged their limitations, and took steps to partner, train, and nurture a diverse workforce that could deliver what a broader segment of their consumers wanted.

“Baby Nancy” manufactured by Shindana Toys, launched in 1968, and sold 15,000 units in three months. One year later, in 1969, they produced 130,000 dolls for kids worldwide. The enterprise grew over the next 15 years to $1.5M with a portfolio of black dolls and action figures that presented versions of black children beyond the negative stereotypes shown to them in the media and their communities. In the 1970s, Shindana Toys became the largest black toy manufacturer in the world. Before closing in 1983 after their founders’ death, Shindana Toys launched a series of coloring books, games, and a multicultural line called “Little Friends” that was a vision of what Mattel would create many years later.

Working Through Bias

With the clear success of Baby Nancy, why did it take Mattel 48 years to diversify its Barbie line? In 1967, Mattel released “Colored Francie,” also known as “Black Francie,” based on another Francie doll with a white complexion and shorter stature than the “real Barbie.” Although “Colored Francie’s” skin tone was the only feature that signified her blackness, her popularity among young black girls soared since they finally had a doll that (sort of) looked like them.

Perhaps this prompted Mattel’s strategic venture with Operation Bootcamp. This is pure speculation, but if we look at the timeline, Mattel seems to be leveraging the insights of its Shindana Toys protégé, begging the question — was Mattel’s interest in Operation Bootcamp altruistic, self-serving, or mutually beneficial?

The same year Baby Nancy launched, Mattel released “Christie” in 1968 and “Nurse Julia” in 1969, both in honor of famed actress Diahann Carroll and her television character. These black dolls had African-American features, much like Baby Nancy, but they were still not designated Barbie. Christie only achieved friend status.

It wouldn’t be until 1980 that Mattel released its first Black and Hispanic Barbies, but they made a critical error. Instead of using the insights gleaned from their Shindana Toys protégé, Mattel simply changed Barbie’s skin tone and not her features. You would have thought Mattel would have learned their lesson, but they continued making “multicultural” dolls using their tried and true caucasian Barbie mold.

As marketers, we can interpret the challenge Mattel faced. For 20 years, they have carefully cultivated Barbie’s image based on a fixed set of ideals and values that conflicted with society’s demand for change and inclusion concerning race and gender. As women shifted their gender roles from homemakers to workforce managers and executives, Mattel slowly built a line of Barbie dolls that included more careers. And as the world started to embrace different cultures, they understood that diversity played an integral role in their bottom line.

Stereotypes were finally getting a toy makeover, yet Barbie continued to iterate with a few uninclusive missteps along the way. For example, in 1997, Mattel partnered with Nabisco to create black and white versions of “Oreo Fun Barbie.” The term “oreo” is offensive to the black community, and they recalled the product. Barbie continued to catch some heat in 1993 around the stereotypical gender-based language used in Teen Talk Barbie and has always been criticized for promoting an unrealistic body image. But in the 2000s, Mattel elevated Barbie’s thinking. She appeared in movies, ran for President several times, won American Idol (I didn’t know Barbie could sing!), and became a Drag Queen. (Her singing chops paid off in the adult market.) However, 2012 would bring a reckoning.

Between 2012-2013, sales dropped 3%, then 6%, and then down to 16% in 2014 when Disney’s Queen Elsa left Barbie out in the cold. The brand no longer held the hearts and minds of its consumers. Barbie was becoming irrelevant. Her perfection became unrelatable.

Rebranding on Diversity

In 2016, the earth shifted. For the first time in 57 years, Barbie got a proper makeover, and her curvy silhouette graced the cover of Time Magazine. A plastic doll’s dream! But there was something different. Mattel grew to embrace the community’s remarkable diversity. It refocused its marketing strategy towards 21st-century American values rooted in Millennials’ earnest desire to move away from screens and towards experiences rooted in play. At the time, then Senior Vice President at Mattel Lisa McKnight said to the HuffPost that millennial parents don’t just want to buy, ”they want to buy-in.”

This, coupled with the demand for representation to achieve brand loyalty, helped Mattel realize financial gains in 2018 as they continued to diversify their line. Mattel released its first gender-neutral doll in 2019 and marketed it as a toy for everyone. In October 2020, in the wake of calls for racial justice, Mattel became bolder with its vision by releasing an animated video of Barbie and Nikki having an honest conversation about race.

Inclusivity is Good For Business

Senior Director of Mattel Consumer Services Gary Cocchiarella said in an interview, “If the parent gets to be the hero, I think we can say ‘mission accomplished.’ Today, Mattel makes Barbie Dolls in over 35 skin tones, 94 hair textures, and nine body types, creating a diaspora of toys that break gender barriers, reduce stereotypes, and open the door to wondrous imagination. While nothing and no one is perfect, Mattel’s willingness to risk mistakes (sometimes egregious and sometimes without proper intention) demonstrates courage. Since 1959, their journey – from their unorthodox willingness to fund and mentor a black business with no experience in toy manufacturing to their rocky transformation into a manufacturer focused on including everyone – serves as a 60-year case study of what it means to celebrate differences. Not to be dismissed or forgotten, the simultaneous success of Shindana Toys provided early evidence of the value of inclusivity and purpose and, in doing so, changed the toy manufacturing industry with their insights and innovation. In 2020, Baby Nancy was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame.

Other iconic brands are starting to embrace color too. On March 26, Sesame Street announced the addition of two black muppets – a father and son duo created to help parents talk about race and racism with their children. Brands that target families have an additional responsibility to create forums and opportunities to tackle the day’s most pertinent issues. Consumers no longer want brands to passively sit on the sidelines. They also want them to have an altruistic hand in developing their kids and fostering good humans, and purpose-driven brands lead the way. So while marketers are growing their company’s profits, they should not remain color-blind to the greater opportunities within your brand’s sphere of influence to create. Gary had it right save one thing. The mission cannot be accomplished if brands don’t join in, and marketers are the bridge that fuels that agenda.

Karen McFarlane specializes in companies that are on the verge of something big. As the Chief Marketing Officer of Kaye Media, Karen helps industrious high-growth businesses push their boundaries and build lasting connections with customers that drive exponential growth and support diversity, equity, and inclusion in the workplace. Through a strategic partnership, Karen is CMO of LetterShop, a creative agency for startups to Fortune 1000. She is President of AMA New York and sits on several non-profit and advisory boards. She was recently named as one of Crain New York’s Most Notable in Marketing and PR.